China’s Information Warfare And Media Influence Sow Division In Thailand – Analysis

By RFA

By Jane Tang

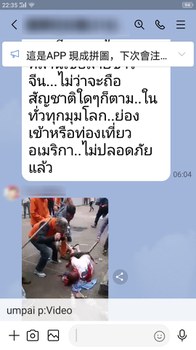

By the time video scenes of a brutal prison riot in Ecuador earlier this year reached Asia, the video’s caption had been changed and read, “American Blacks and Whites in California Killing Chinese,” and the clip went viral.

Disinformation like that video, doctored to promote anti-U.S. hatred, is now growing in Thailand, say media researchers.

Chinese narratives, whether fake news or state-sponsored propaganda, are gradually seeping into Thai media, academia, and political and business circles, and people from different sectors in Thailand are expressing concern over the phenomenon, experts say.

In the violent video, an Asian man is seen lying on the ground covered in blood and with his face wrenched in pain. Dozens of Spanish-speaking men attack him with bats and sticks, beating him in broad daylight.

No source is cited in the video, which was described in the post as a hate crime against Asians in America, and went viral on social media platforms. Since mid-April, it has been shared widely in Southeast Asian chat groups and on Taiwanese and Chinese social media and instant messaging apps.

The common theme on all the comment threads was “What’s Wrong with the United States?”

After reviewing messages circulating in Chinese WeChat groups; chat groups on Line, the instant message app popular in Asia; and Facebook groups, an RFA reporter found that the video had targeted audiences in China, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia with inflammatory anti-U.S. captions.

“America is out of order! In California, U.S.A., blacks and whites are killing Chinese. Forward this video all over China!” read one.

“A Chinese lost his life meaninglessly, but our country is still trying to please the U.S. for favors,” said another.

“Time for Chinese in the U.S. to wake up. Escape from America as soon as possible. Return to China or emigrate to a Southeast Asian country — the sooner, the better,” said yet another.

These doctored messages and graphic videos have stirred up significant reactions in the Chinese community in Thailand and also translated into the Thai language.

“Facebook groups and Line are the most popular sources of information in Thailand, especially for the older generations,” said Teeranai Charuvastra, a Bangkok-based journalist and board member of the Thai Journalists Association.

Over the past year, distorted “anti-America” and “Hate Americans” videos have become common in Thailand, he told RFA, noting that while sophisticated younger-generation audiences were unlikely to buy stories like these, older people are more susceptible to media manipulation.

From Russia to Southeast Asia via China

After investigating the source of this video and its paths of transmission, RFA found that what the video had captured was a prison riot in Ecuador on Feb. 23, and it had been uploaded to Twitter by an official of the Ecuadorian Ministry of Justice.

On March 14, the video was shared on Russian instant messaging software and on Telegram. By late April, the video had surfaced on instant messaging software and social media in China, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia.

The video also appeared on Reddit, a U.S. forum, where it was mistakenly described as a violent incident in Los Angeles. However, the account that uploaded the video has since been deleted.

Lilly Lee, an independent researcher who has been following Chinese Communist Party (CCP) information warfare, pointed out that the dissemination of distorted information fits two main themes of recent CCP information warfare.

China seeks to fortify the narrative that the Chinese governing model is better than that of Western democracies during the pandemic, and it works to manipulate recent hate crime incidents against Asians in America – widely covered in the U.S. media – to promote China as the power best suited to maintain world order.

“China wants to create a narrative that China, as the big brother, will protect Chinese people and all ethnic Chinese populations,” Lee told RFA.

In CCP information warfare, whether the message is to smear the U.S. as a chaotic country or to praise China, all push a broader narrative that serves the party: “Democracy is not a good way to rule the people in a country,” she said.

Lee added, however, that unlike Russia, whose information warfare is largely operated directly by Russian government agencies, China’s disinformation work is diffuse, and often delegated to various departments or outsourced to private contractors.

Western analysts long focused on Russian disinformation efforts have also started to come to grips with relative latecomer China’s aggressive campaign.

“Beijing uses large numbers of fake social media accounts to push its messages. It has increasingly relied on the types of trolls and bots Russia has utilized. Chinese diplomats amplify spin and outright false messages, and big Chinese state media outlets push the government’s stories,” said a September 2020 report by the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR).

The quality of Chinese disinformation efforts is inconsistent, and falsehoods can be easily detected.

In Taiwan, a prime target of information warfare to reinforce Beijing’s efforts to induce the democratic island to accept unification with the communist mainland, awareness of China’s campaign is high and fact-checking mechanisms are being improved, the Ecuador video did not attract much reaction.

Last month, Taiwanese authorities unveiled a falsified Taiwan Presidential Office memo claiming that Taipei had agreed to receive nuclear wastewater from Fukushima, Japan. But the message used the mainland’s simplified Chinese characters instead of traditional script used in Taiwan, and employed terms that betrayed unfamiliarity with government agencies and titles on the island.

Some Chinese ‘punches are landing’

And in March, the most famous of the aggressive official Twitter accounts of China’s pugnacious “Wolf Warrior” diplomats – that of foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian – tweeted a conspiracy theory suggesting that the coronavirus originated in the U.S.. Zhao also stirred controversy in late 2020 when he shared a fake image of an Australian soldier killing an Afghan child.

“Chinese disinformation still seems more simplistic than Russia’s. Chinese fake social media accounts spreading disinformation about COVID-19 often appear shoddier than Russian ones and thus easier to expose,” said the CFR report.

“Still, some of Beijing’s disinformation punches are landing,” it noted.

RFA was unable to obtain an official Chinese comment on the Thai fake news campaign, but foreign ministry spokespersons have responded to previous accusations that China spreads disinformation by saying the country is a victim of fake news, not a perpetrator, and accusing the platforms of having double standards by not blocking unfavorable news reports about China. China blocks Twitter and Facebook but its official media and diplomats use the platforms to spread Chinese views and combat critics.

The same Ecuador prison riot video that barely caused a ripple in Taiwan ignited passions in Thailand, however, where it went viral.

Thailand became fertile ground for the disinformation video because conspiracy theories about the U.S. were already circulating widely since a Thai student movement erupted after the dissolution in February 2020 of the Future Forward Party. The destruction of the new progressive political party favored by younger Thais triggered the largest wave of pro-democracy protests in Thailand since 2014.

Social media disinformation campaigns said the Thai students were incited by Washington, while more outlandish stories alleged Western-led collusion between the Thai student movement and the 2019-20 Hong Kong pro-democracy movement, whose leading activists were also branded Western puppets by China’s online troll army.

In August 2019, Twitter announced it had banned 936 accounts originating from within China that “were deliberately and specifically attempting to sow political discord in Hong Kong, including undermining the legitimacy and political positions of the protest movement on the ground.”

The U.S. tech giant said it made the decision based on “reliable evidence to support that this is a coordinated state-backed operation.” The 936 frozen accounts followed the proactive suspension of “a larger, spammy network of approximately 200,000 accounts,” it added.

Facebook at the same time suspended a smaller page of pages, groups and accounts focused on disinformation about Hong Kong protests.

“Although the people behind this activity attempted to conceal their identities, our investigation found links to individuals associated with the Chinese government,” the social media platform said.

To the 33-year-old Thai journalist Teeranai, “the most unfortunate thing is that these infowars are very distracting,” he said.

Instead of debating issues critical to the future of the nation of 69 million people, “the public was wasting time discussing who was behind the student movements, questioning whether the U.S. and other Western countries were meddling in the matter, or accusing the student protesters as gangsters or paid actors,” he added.

“The danger of this misinformation and disinformation is that they scandalized the activists, who in turn lost their own credibility and the general public’s trust in the movement,” added Teeranai .

Beyond the fake news campaigns, analysts in Thailand are also concerned about the longer game China is playing to influence public opinion: the expansion of CCP-owned media in Thailand.

Chinese official media are required to demonstrate strict loyalty to the CCP and to Chinese President Xi Jinping. In the 2021 World Press Freedom Index released by Reporters Without Borders, a press-freedom watchdog, China ranked near the bottom in the world, above only Turkmenistan, North Korea and Eritrea, while the number of journalists detained in China is the largest in the world.

In 2015, the Chinese government made “media and information cooperation” with the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) an essential part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Xi’s signature global infrastructure program to support trade with China.

In the following years, through mergers and the acquisition of Thai media outlets or through signing MOUs, China began providing free content to TV stations in Thailand from party-controlled outlets Xinhua News Agency and China Central Television (CCTV).

Conspiracy theories as straight news

In 2019, against the backdrop of the “China-ASEAN Year of Media Exchanges,” content from Xinhua was published in Khaosod, the third-largest newspaper in Thailand. Bangkok-based journalist Tyler Roney observed as a result that the Thai newspaper completely adopted Beijing’s narrative when reporting on the massive pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong.

By 2020, Thai media had become even further under Beijing’s influence when covering reports regarding the source of the COVID-19 pandemic, in at least one case running a conspiracy theory pushed by CCTV’s global arm, CGTN.

“Some Thai media just put the conspiracy theory generated by the Chinese state media as news reports. For example, ‘Bombshell Report: The Coronavirus May Have Come from American Soldiers.’ Such so-called news reports did not verify the news sources. They also ignored the fact that the source of information came from Chinese authority controlled state-run media,” said Teeranai.

James Gomez, director of the Thai think tank Asia Centre, said that compared with Taiwan and Japan, where citizens are on high alert against disinformation and misinformation from foreign powers, in Thailand, the public lacks the ability to identify information from China, while the government does nothing to counter Chinese public opinion influence efforts.

“Thai government agencies and elites are closely aligned with China in order to gain economic, military, or political benefits,” Gomez told RFA.

“Therefore, they will not criticize China, nor will they use ‘interference from foreign powers’ to describe China. I think this is exactly where the problem lies: Authorities are unwilling to acknowledge the impact on the local level caused by the Chinese narrative.”

Chinese-Thai economic relations have deepened in recent years, and China has become the major source of international students for Thai universities, tourists and investment.

In 2019, Chinese tourists made up 27.6 percent of Thailand’s foreign visitors, and the China-Thailand high-speed railway program brought in supporting factories and investments. In 2020, China surpassed Japan to become Thailand’s major source of Foreign Direct Investment.

A poll by Japan’s Nikkei Asia earlier this year found that when asked how they would choose between the U.S. and China, the Thai people showed a 50-50 split.

“To a certain degree, this also reflects the principle of equilibrium that Thailand has historically practiced in its foreign policy when dealing with superpowers,” said Poowin Bunyavejchewin, a senior researcher at the Institute of East Asian Studies at Thammasat University.

In contrast to elites, many citizens in the Nikkei survey expressed concern about China’s growing influence in Southeast Asia and in Thailand, about the quality of the planned high-speed rail line, about a possible debt trap, and about China’s (COVID) vaccine diplomacy.

Poowin also feels uneasy at the way he says Chinese funding is entering Thai academia in a non-transparent manner.

“During the past five years or so, I feel like there was a Chinese Communist Party spokesperson in Thai academia,” Poowin said. “What they told the public was not fact-based truth, nor was it most suitable for Thailand’s true national interests. But they dominate the opinions.”

Gomez of the Asia Centre said he shares the concern that diversified voices are being muffled in Thailand, and fears this will take a toll on a civil society already under pressure from authoritarian military leaders.

“I think if the trend continues, there will be no room left for freedom of expression in Thai society,” said Gomez.

Reported by Jane Tang for RFA’s Mandarin Service. Translated by Min Eu.