The US Army’s Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW): Dark Eagle – Analysis

By CRS

By Andrew Feickert

What Is the Army’s Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon?

The Army’s Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW), also known as Dark Eagle (Figure 1), with a reported range of 1,725 miles, consists of a ground-launched missile equipped with a hypersonic glide body and associated transport, support, and fire control equipment.

According to the Army, “This land-based, truck-launched system is armed with hypersonic missiles that can travel well over 3,800 miles per hour. They can reach the top of the Earth’s atmosphere and remain just beyond the range of air and missile defense systems until they are ready to strike, and by then it’s too late to react.”

The Army further notes, “The LRHW system provides the Army a strategic attack weapon system to defeat Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) capabilities, suppress adversary long-range fires, and engage other high payoff/time critical targets. The Army is working closely with the Navy in the development of the LRHW. LRHW is comprised of the Common Hypersonic Glide Body (C-HGB), and the Navy 34.5-inch booster.”

LRHW Components

Missile

The missile component of the LRHW is reportedly being developed by Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman. When the hypersonic glide body is attached, it is referred to as the Navy-Army All Up Round plus Canister (AUR+C). The missile component serves as the common two-stage booster for the Army’s LRHW and the Navy’s Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS) system, which can be fired from both surface vessels and submarines.

Common Hypersonic Glide Body (C-HGB)

The C-HGB is reportedly based on the Alternate Re-Entry System developed by the Army and Sandia National Laboratories. Dynetics, a subsidiary of Leidos, is currently under contract to produce C-HGB prototypes for the Army and Navy. The C-HGB uses a booster rocket motor to accelerate to well above hypersonic speeds and then jettisons the expended rocket booster. The C-HGB, which can travel at Mach 5 or higher on its own, is planned to be maneuverable, potentially making it more difficult to detect and intercept.

LRHW Organization and Units

The LRHW is organized into batteries. According to the Army, “a LRHW battery consists of four Transporter Erector Launchers on modified M870A4 trailers, each equipped with two AUR+Cs (eight in total), one Battery Operations Center (BOC) for command and control, and a BOC support vehicle.”

The 5th Battalion, 3rd Field Artillery Regiment at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington, was designated to operate the first battery of eight LRHW missiles. The battalion, also referred to as a Strategic Long-Range Fires battalion, is part of the Army’s 1st Multi Domain Task Force (MDTF), a unit in the Indo Pacific-oriented I Corps stationed at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, WA. Other LRHW batteries are planned for Strategic Long-Range Fires battalions in the remaining MDTFs scheduled for activation.

LRHW Testing and Program Activities

According to a 2023 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) Study, “U.S. Hypersonic Weapons and Alternatives,” “Extensive flight testing is necessary to shield hypersonic missiles’ sensitive electronics, to understand how various materials perform, and predict aerodynamics at sustained temperatures as high as 3,000° Fahrenheit.”

The Army originally planned for three flight tests of the LRHW before the first battery fielding in FY2023. On October 21, 2021, the booster rocket carrying the C-HGB vehicle reportedly failed a test flight, resulting in what defense officials characterized as a “no test” as the C-HGB had no chance to deploy. Reportedly, a June 2022 test of the entire LRHW missile also resulted in failure.

Flight Test Delays

In October 2022, it was reported the Department of Defense (DOD) delayed a scheduled LRHW test in order to “assess the root cause of the June [2022] failure.” Reportedly, the delayed test would be rescheduled to the first quarter of FY2023.

March 2023 LRHW Test Scrubbed

On March 10, 2023, it was reported, “On March 5, DOD was preparing to execute Joint Flight Campaign-2 featuring the Army version of the prototype weapon launched at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, FL, when the countdown was halted…. As a result of pre-flight checks during that event, the test did not occur.”

Cancelled September 2023 LRHW Test and Program Delay

On September 6, 2023, it was reported, “The DOD planned to conduct a flight test at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida, to inform hypersonic technology development. As a result of pre-flight checks, the test did not occur.”

On September 14, 2023, in an Army statement to Bloomberg News, the Army reportedly acknowledged it would not be able to meet its goal of deploying the LRHW by the end of FY2023.

Change in LRHW Testing Pathway

In late November 2023, Navy and Army acquisition executives reportedly decided to “revamp efforts to prepare for [LRHW] flight test following three flight test attempts this year that were scrubbed because of problems with the Lockheed Martin-produced launcher.” The Army’s new testing approach will feature subcomponent testing. It was also noted the new testing effort was “definitely going to be months, not weeks,” and could possibly run into next summer.

LRHW Fielding Delayed Until FY2025

According to a June 2024 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report to Congress, “The Army missed its goal of fielding its first LRHW battery—including missiles— by fiscal year 2023 due to integration challenges. Based on current test and missile production plans, the Army will not field its first complete LRHW battery until fiscal year 2025. Before the Army can field an operational system, it must conduct a successful end-to-end missile flight test using the Army’s launch system.”

GAO further notes, “The LRHW integration issues discovered during testing also affect missile production. The Army cannot complete the missiles for the first battery until a successful test demonstrates that the current design works. LRHW officials stated that once a successful flight test is achieved, the first production missile will be delivered within approximately six weeks and the first battery of eight missiles will be delivered within approximately 11 months. If the Army discovers issues with missile performance in flight testing, missile deliveries and the fielding of the first operational LRHW system could be further delayed.”

Considerations for Congress

Possible oversight considerations for Congress could include:

LRHW Testing and Fielding Concerns

The Army’s November 2023 decision to revise its LRHW testing methodology seemingly suggests past testing difficulties might have been more significant than previously believed. GAO’s June 2024 report stated that LRHW fielding would again be delayed – contingent on the Army successfully achieving a number performance goals and tests. Another potential concern is, according to GAO, after a successful test flight “the first production missile will be delivered within approximately six weeks and the first battery of eight missiles will be delivered within approximately 11 months,” which arguably could be considered “aggressive” given past LRHW test performances. In consideration of the LRHW’s developmental and testing history, policymakers could decide to further examine the Army’s LRHW flight test plans. One potential issue for examination could be theArmy’s rationale and technical justification for transitioning the LRHW into production within six weeks of a successful test flight. Another concern could be what are the Army’s contingency plans if the LRHW is unable to overcome current “integration challenges.”

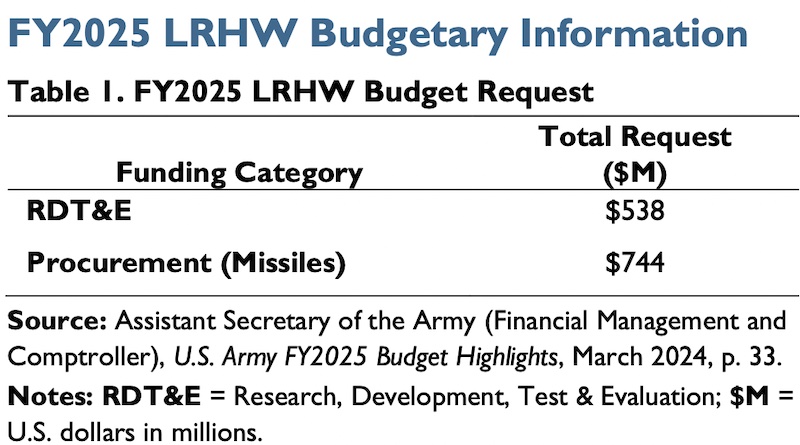

LRHW Missile Costs

According to a January 2023 Congressional Budget Office study, “U.S. Hypersonic Weapons and Alternatives,” purchasing 300 Intermediate-Range Hypersonic Boost- Glide Missiles (similar to the LRHW) was estimated to cost $41 million per missile (in 2023 dollars). A January 2023 Center for Strategic and International Studies report, “The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan,” noted when discussing hypersonic weapons, contends “their high costs limits inventories, so they lack the volume needed to counter the immense numbers of Chinese air and naval platforms.”

Given concerns about how LRHW missile costs could influence LRHW inventories, policymakers might decide to further examine LRHW missile costs as well as quantities of LRHW missiles needed to support potential combat operations in various theaters of operations.

- About the author: Andrew Feickert, Specialist in Military Ground Forces

- Source: This article was published by the Congressional Research Service (CRS)