Radicalization In Central Asia: From Roots To Repercussions – Analysis

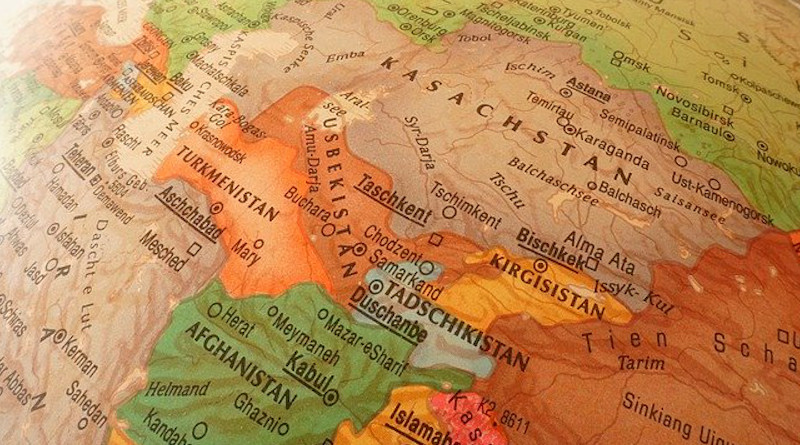

Central Asia is a region situated between the Oxus River in the west and China’s Xinjiang province in the east, bordered by Russia to the north and Afghanistan to the south. This region has a long and rich history of settlements, dating back to the Huns, Shakas, and Parthians, followed by the spread of Islam. It later witnessed the rise of powerful empires, including those of Genghis Khan, the Timurid dynasty, and the Seljuks. In the 1860s, Tsarist Russia occupied Central Asia, eventually integrating it into the Soviet Union after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

During the Cold War, the region became a focal point of the “Great Game” between the expansionist USSR and the British Empire. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Central Asia gained independence, giving rise to five republics: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The shifts in political authority over time significantly impacted the region’s socio-political landscape, including the role and practice of Islam.

The relationship between Islam and Central Asia is both long-standing and complex. Islam entered the region during the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates in the 8th century through Arab invasions and Sufi missionary activity, becoming a key component of the region’s political and social fabric. The liberal Hanafi school of jurisprudence gained prominence across Central Asia. While the region saw various Islamic empires and dynasties, the only period when Islam’s dominance was significantly curtailed was under Mongol rule, as the Mongols adhered to their own legal code, Yassa. The decline of Islam’s political authority began in the 19th century with Tsarist Russia’s expansion into Central Asia. The October Revolution of 1917 further marginalized Islam, significantly weakening its influence in the socio-political framework of the region.

However, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 triggered a rapid resurgence of Islam, driven by factors such as the Afghan crisis, the 9/11 attacks, and the subsequent U.S.-led Global War on Terror (GWOT). This article explores the theoretical frameworks, causes, and phases of Islamic revival in Central Asia, along with the factors contributing to its radicalization. Additionally, it examines the measures adopted by Central Asian regimes to curb radicalization and evaluates their effectiveness in achieving the desired outcomes.

Theoretical Framework of Radicalization

“Radicalization” is a highly contested concept, often defined and interpreted in varying ways within academic and policy literature. Many scholars conceptualize radicalization as a process marked by an increasing commitment to extremist ideologies and the use of violent means in political conflicts. From this perspective, radicalization involves a shift towards polarized and absolute interpretations of social or political issues, often leading to the adoption of radical aims and objectives. This transformation may stem from hostility towards specific social groups, institutions, or state structures and can result in an increasing reliance on violence.

Radicalization encompasses both behavioral (actions) and ideological (beliefs and perceptions) dimensions, which, while closely linked, do not necessarily correspond or depend on each other. In modern times, radicalization serves as the breeding ground for terrorism, as any violent attack against the state is classified as a terrorist act. It manifests as an extreme ideology expressed through violent means.

McCauley and Moskalenko define radicalization as follows: “Functionally, political radicalization is increased preparation for and commitment to intergroup conflict. Descriptively, radicalization means change in beliefs, feelings, and behaviors in directions that increasingly justify intergroup violence and demand sacrifice in defense of the group.”

Several theoretical perspectives help explain the rise of radicalization, particularly in the Central Asian context.

Social Strain Theory

Social strain theory, developed by sociologist and criminologist Robert K. Merton and later expanded by Robert Agnew, posits that when a political system prevents individuals or groups from attaining socially accepted goals—such as political participation or access to power—it generates strain that can push individuals towards violence. This theory suggests that societal structures create conditions that may lead to criminal behavior as a response to perceived injustices.

Agnew highlights that one significant source of strain is the government’s repression of legitimate demands, particularly when citizens are denied political agency or social mobility. In the Central Asian context, social strain theory provides a framework to examine the rise of Islamic radicalization, as state-imposed restrictions on religious and political freedoms create conditions that may fuel extremism.

Frustration-Aggression Hypothesis

The frustration-aggression hypothesis, as outlined by Friedman and Schustack, asserts that while frustration may not always lead to aggression, aggression is almost always a product of frustration. Behavioral psychologists argue that aggression is instinctive and that when individuals or groups encounter obstacles preventing them from fulfilling their legitimate needs or aspirations, frustration can escalate into anger and violence.

Cognitivist scholars describe this frustration as a “blocked goal.” One concrete example of such obstruction is severe political repression that restricts political participation and suppresses political or religious identity. Johan Galtung’s concept of structural violence—violence embedded within social structures and institutions—further explains how systemic repression can lead to extremist responses. Galtung argues that structural violence, such as restrictions on religious practices or identity suppression, can ultimately give rise to direct violence, including religious extremism.

While scholars use this theory to explain Islamic radicalization in Central Asia, its applicability remains a subject of debate. Nonetheless, both social strain theory and the frustration-aggression hypothesis provide crucial insights into the dynamics of radicalization in the region, particularly in the context of state repression, political exclusion, and socio-economic grievances.

Phases of Radicalization in Central Asia

Islam was introduced to Central Asia in the seventh century and solidified its dominance by the mid-eighth century. Historically, two distinct variants of Islam emerged in the region: one associated with the urban centers of Samarkand and Bukhara, and the other prevalent in the tribal zones. The former, shaped by the religious institutions (madrassas) of Samarkand and Bukhara, was often characterized by a more orthodox interpretation of Islam, with the clergy playing a dominant role in religious affairs. In contrast, Islam in the tribal regions spread primarily through Sufi brotherhoods such as the Yasawiyya, which facilitated its gradual assimilation into local traditions.

The global political landscape of the late 20th century witnessed the increasing politicization of Islam, particularly following the Iranian Revolution. Events such as hostage crises, attacks on Western embassies, and other violent acts perpetrated by Islamist militants contributed to the perception of Islam as an increasingly militant force. Political unrest among Muslim populations in the former Soviet Union, the Caucasus, the Balkans, Xinjiang (China), Palestine, and North Africa reinforced fears of an emerging radical Islam. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Islam re-emerged as a potent socio-political force in Central Asia, filling the ideological vacuum left by Communist rule.

Islam under Soviet Rule

During Soviet rule, Islam was subjected to severe repression, yet it remained resilient despite state-imposed restrictions. Mosques were systematically demolished, repurposed, or closed, while young Muslims were encouraged to participate in Soviet youth organizations instead of religious institutions. Stalin’s policies were particularly harsh, with a significant crackdown on religious activities beginning in 1927. However, in 1943, the Soviet authorities established the Spiritual Directorate of Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan (SADUM) to exert control over religious practices.

Following Stalin’s death, two major offensives against Islam were undertaken. Under Khrushchev (1958–1964), approximately 25% of official mosques were closed, with Tajikistan (16 out of 34 mosques) and Uzbekistan (23 out of 90 mosques) experiencing the most severe impact. Conversely, in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, only one mosque in each republic was shut down, while all four official mosques in Turkmenistan remained open. These figures illustrate the relative strength of Islamic identity in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan compared to the other Central Asian republics.

The final major Soviet crackdown on Islam occurred in 1986 under Gorbachev. However, by this period, a broader trend of liberalization had already taken hold, limiting the effectiveness of state suppression. Under Soviet rule, Central Asia remained largely peripheral to the global Islamic world, isolated from key geopolitical developments such as the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and the Iranian Revolution. Consequently, when the Central Asian republics gained independence in 1991, the majority of their populations had only a rudimentary understanding of Islamic doctrines.

With the reopening of borders in the early 1990s, Central Asia found itself reintegrated into the wider Islamic world. However, political elites in the region often lacked deep knowledge of Islam, having been shaped by decades of Soviet secularism. Amid the ideological vacuum left by the collapse of Communism, many ordinary citizens turned to religion as a means of making sense of their national identity and the uncertainties of independence.

Three key observations can be made regarding the trajectory of Islam in post-Soviet Central Asia:

- Despite Soviet-era repression, the majority of Central Asians continued to identify as Muslims. Scholar Martha Brill Olcott argues that an awareness of Islamic heritage remained integral to Central Asian identity, even among individuals with limited religious knowledge or practice.

- The revival of religious practices in the late 1980s was not an external imposition but rather a re-emergence of long-suppressed cultural and religious traditions. As Olivier Roy notes, this revival was an “outward manifestation of a culture and religious practice that never completely vanished.”

- The rise of extremist Islamist organizations in the region was not entirely due to foreign influence. Several militant networks, such as Adolat (Justice), Tawba (Repentance), and Islam Lashkarlari (Warriors of Islam), had already operated underground during the Soviet era and resurfaced in the wake of political liberalization.

The Fergana Valley: A Hub of Islamic Revivalism and Radicalization

The Fergana Valley, a fertile and densely populated region spanning Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, has been the focal point of Islamic revivalism and radical movements in Central Asia. During the Soviet era, the borders between these republics were largely symbolic, allowing for free movement across the region. However, in the post-Soviet period, as tensions between the newly independent states increased, these borders became heavily fortified with barbed wire and landmines.

As a historically significant political and cultural center, the Fergana Valley has witnessed the emergence of various nationalist and Islamist movements. The Uzbek nationalist dissident party Birlik was once active in the region but was later suppressed by the Uzbek government. More radical organizations such as Adolat, Tawba, and Islam Lashkarlari also originated in the valley, serving as precursors to the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and Hizb ut-Tahrir (HT). While these groups varied in ideology and tactics, they shared a common objective of replacing secular governance with an Islamic state.

Due to sustained government crackdowns, many radical Islamists from the Fergana Valley sought refuge in neighboring Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, as well as in Afghanistan and Pakistan—regions that later became crucial hubs for jihadist movements. These individuals played a key role in propagating radical Islamic ideologies among broader populations.

Scholars such as Bernard Lewis argue that Central Asian governments have often overgeneralized Islamic activism, conflating devout believers with radical militants. However, significant ideological and strategic differences exist among various Islamist groups. For instance, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) maintained strong ties with the Taliban and later with Al-Qaeda, actively engaging in violent insurgency. Conversely, Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islamiyya advocated for an Islamic caliphate but officially promoted nonviolent methods.

Although some Islamist factions have found common ground in opposing secular governments, they have frequently been divided by ideological, personal, and financial disputes. This tendency toward fragmentation has made it difficult to study these movements comprehensively. Nonetheless, broad categories can be identified, distinguishing violent extremist groups from those that pursue their objectives through political or social activism.

Implications

The issue of radicalization has had a significant impact across the Central Asian region, though its effects have varied in intensity. Following the suppression of Islamist movements in the 1990s and 2000s, hundreds of individuals from the region migrated and joined transnational extremist organizations such as ISIS and the Taliban. This phenomenon has influenced Central Asia in multiple dimensions—politically, socially, and in terms of regional and international security.

Political Implications

The rise of radicalization in Central Asia has had profound political consequences, particularly in terms of governance and stability. The perceived threat of extremism provided an opportunity for authoritarian leaders to consolidate their power under the pretext of maintaining order. This was particularly evident in the regimes of Emomali Rahmon in Tajikistan and Shavkat Mirziyoyev in Uzbekistan, where autocratic measures were reinforced to suppress opposition. Consequently, political rights and civil liberties were increasingly curtailed, leading to a significant decline in democratic institutions and public participation in governance. The justification of counterterrorism measures further facilitated the suppression of political dissent and the weakening of civil society.

Social Implications

Radicalization has also had deep social repercussions in Central Asia, contributing to sectarian and ethnic divisions. The rise of religious extremism has exacerbated interfaith tensions, fostering an environment of social intolerance. Additionally, ethnic disparities have widened, particularly affecting the ethnic Russian population, whose numbers declined significantly after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. The phenomenon has also deepened socioeconomic inequalities, further alienating the economically weaker sections of society from the elite. In some nations, radicalization has contributed to the emergence of a more rigid and conservative societal framework, restricting social freedoms and altering traditional cultural norms.

Security Implications

The security landscape of Central Asia has been profoundly affected by radicalization, with the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) playing a crucial role in shaping regional security dynamics. China, under the pretext of counterterrorism, has expanded its influence in Central Asia, engaging in direct and indirect interventions to secure its strategic interests. Since 2001, Beijing has systematically increased its presence in the region, particularly in the Fergana Valley, where it has capitalized on existing vulnerabilities. The Chinese government has established a network of security and economic initiatives aimed at exerting greater control over the region, further entrenching its geopolitical ambitions under the guise of regional stabilization efforts.