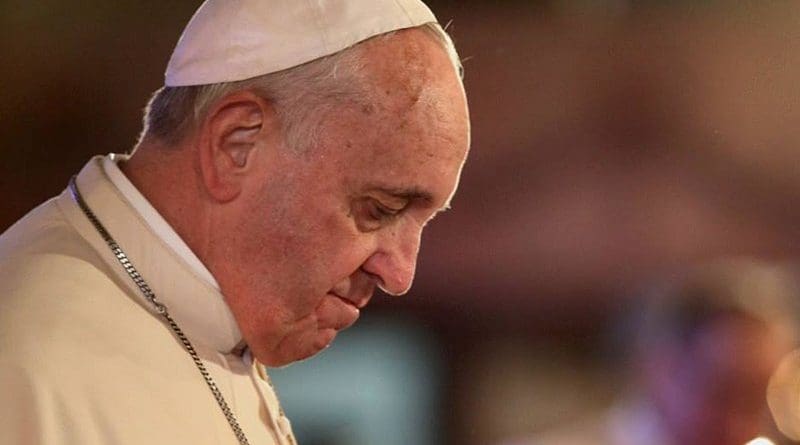

Pope Francis’ Visit To Budapest: Political Or Pastoral? – Analysis

Pope Francis will visit Hungary on April 28-30, even as Viktor Orban seeks to assert more political control over the church and at the risk that any ‘peace message’ by the Pope over the war will be used for the PM’s own propaganda

By Alexander Faludy

Pope Francis’s trip to Budapest this week is welcome news to many of Hungary’s Catholics, who felt short-changed by the mere five hours the pontiff spent in Budapest in 2021 en route to a three-day visit to Slovakia. Yet the diplomatic and political context this time is different – and more of a source of concern to onlookers.

The body language on show in photos of Francis’s short 2021 protocol-meeting with the populist Prime Minister Viktor Orban before attending the closing Mass of that year’s International Eucharistic Congress convey a strained atmosphere.

Both leaders sent pointed signals. Orban gave Francis a copy of a 1243 letter from Hungary’s King Bela IV, asking Pope Innocent IV for help repelling Mongol invaders – a possible dig at the pope’s welcoming attitude to migrants. Francis’s homily at the Mass warned against the “false messianism” of worldly power that seeks “to silence opponents” – a seeming reference to the country’s creeping autocratisation and silencing of the media under the Fidesz government over the last 13 years.

Since then, Budapest has made a concerted effort to woo the Vatican in a ‘hearts and minds’ campaign’ spearheaded by Eduard von Habsburg, Hungary’s ambassador to the Holy See and a scion of Austria-Hungary’s once ruling family. Habsburg’s personal charm and moderate language is far removed from the pugilistic image cultivated by Hungary’s foreign minister, Peter Szijjarto.

Habsburg has won the confidence of high-ranking staff in the Vatican’s central administration, developing a notable rapport with Archbishop Richard Gallagher, the Vatican’s secretary for relations with states (basically, the foreign minister).

Many subordinate staff in the Vatican’s diplomatic corps, however, remain wary of engaging with the Hungarian government, a Vatican correspondent told BIRN this week.

Partners in ‘peace’

Personal affability would not, however, have been enough to secure the sea change in Vatican-Hungary relations which has occurred over the last 18 months.

A number of changes in communication and policy cooperation have been needed to bring about a reset. Fidesz has been at pains to find common ground with the Vatican, for example through its natalist “Family Policy”, opposition to “LGBT ideology”, and humanitarian assistance to persecuted Christian communities in the Middle East and Africa.

Since 2021, the venomous, sometimes relentless attacks on Francis published in Hungary’s Fidesz-controlled media outlets has vanished. The completeness of the disappearance reveals the centrally directed nature of their former occurrence.

Where once Hungarians could read columns by Fidesz co-founder Zsolt Bayer deriding Francis as “a senile old fool or a scoundrel” working with the Hungarian-born US financier George Soros to undermine Christian nations, they are now treated to Orban reminding his listeners that in Europe only he and Pope Francis are “on the side of peace”, as demonstrated by their shared calls for an immediate ceasefire in Ukraine.

It is with regard to Ukraine that Francis’s visit is most vulnerable to political manipulation at a time when Orban is coming under heavy pressure from NATO allies and EU partners on account of his seemingly pro-Russian stance. Although Hungary has condemned the invasion formally, Orban’s conduct has often seemed to fall short of being sympathetic to Ukraine’s plight or even being neutral.

Hungary’s government has blocked EU sanctions against key Kremlin associates like Patriarch Kiril, delayed the progress of Ukraine’s security partnership with NATO and, until this week, tolerated the presence of Russia’s International Investment Bank in Budapest, despite the latter’s perception by NATO partners as a “spy bank” whose diplomatic status is alleged to have afforded ideal cover for espionage activities.

Pope Francis’s call for an immediate ceasefire in Ukraine, which would in practice presently favour Russia, is well understood to proceed from the principles of Catholic Social Teaching and a concern for the sanctity of human life. Conversely, Orban’s use of the language of peace tends to be greeted with scepticism and redolent of the Cold War “peace movement” that was widely used as cover for Soviet-influence operations.

As this visit is the first that Francis has made to a country immediately neighbouring Ukraine since the start of Russia’s war, any delivery of a strong peace message in Budapest could play into an agenda other than the pope’s own. It could even undermine the steps he has taken in recent months to balance his remarks with clear affirmation of Ukraine’s right to proportionate self-defence against armed aggression.

Some Catholic voices in Hungary that are critical of the government acknowledge the danger while at the same time believing the pope can ultimately swerve it.

Andras Hodasz is one of those voices. Hodasz left the Catholic priesthood last year after speaking out against the increasing interference by Orban’s Fidesz party in the country’s churches. For example, in the run-up to the April 2022 election, which took place in conjunction with a referendum on LGBT issues scheduled for election day, the Hungarian Catholic Bishops’ Conference issued a statement on marriage that Catholic intellectuals said far exceeded the affirmation of traditional teachings on heterosexual marriage, claiming it to be “the foundation of human dignity”. The idea for the statement is understood to have come not from within the Bishops’ Conference, but, rather, from the office of the prime minister.

Hodasz, the only cleric to object on record, then faced a backlash from the church hierarchy that feared his outspokenness could endanger generous government funding of church social institutions.

Hodasz predicts both that the Hungarian government will attempt to manipulate the visit and that Francis will remain his own man – or rather God’s.

In an opinion piece for the independent media portal Telex looking towards the Pope’s visit published on Palm Sunday (April 2), Hodasz drew parallels between Jesus’s entry to Jerusalem and Francis’s visit to Budapest. Francis, he wrote, “Like Jesus will not allow himself to be exploited by one side or the other for the political interests of the moment.”

Soft on autocrats

Yet, while Hodasz’s optimism is heartening, others fear it might be misplaced.

Francis has a track record of credulousness when it comes to the overtures of authoritarian leaders who have learnt how to mimic his own talking points.

According to the religious affairs journalist Jonathan Luxmoore, who writes regularly on papal diplomacy for the Church Times, “Vatican diplomats often show a weak understanding of real conditions on the ground. The problem is acute today, as seen by the Vatican’s dealings with China, Belarus, and other dictatorial and totalitarian regimes.”

This is also true in respect of visits and compliments the pope has exchanged with the leaders of Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, both close allies of Orban. Critics say these have helped obscure the dire human rights records of both and lent them a patina of respectability.

Hungary maintains strong ties with both countries bilaterally and via the Turkic Council, whose European Representation Office is hosted in Budapest at public expense.

There is, thus, every chance that the Hungarian authorities have studied the playbook used by their Central Asian allies and will look to implement it for themselves.